Abstract / Table of contents

The purpose of this article is to show that:

The Virginal Conception of Christ must be defined accurately and contrasted with false views

The Virginal Conception was prophesied in the OT and fulfilled in the NT

The Gospel accounts of the birth of Christ are harmonisable and historically reliable

The alleged silence of Mark, John and Paul does not disprove the doctrine

The theory that the gospels are midrash has no factual basis

The Virginal Conception was not borrowed from pagan mythology

The Virginal Conception of Christ

First published in: Apologia 3(2):4–11, 1994;

last updated 24 December 2014

1) Definition

When biblically-informed Christians talk about the ‘Virgin Birth’ they really mean the ‘Virginal Conception’ (Virginitas ante partum), i.e. that Christ, the Second Person of the Trinity Incarnate, had no human biological father. The doctrine of the Virginal Conception is scriptural and affirmed by early Christians such as Ignatius (d. AD c. 108), Justin Martyr (c. 100 – c. 165), Irenaeus (c. 130 – c. 200), and Tertullian (c. 150 – c. 212). But there was nothing miraculous about the birth. The true doctrine of the Virginal Conception must be distinguished from some false views:

a) Virginitas in partu: Mary gave birth in such a way as to avoid labour pains and leave her hymen intact. This was first found in the gnostic Ascension of Isaiah (late 1st century),1 and also found in the late 2nd century Protoevangelium of James. Among early Christian writers it was cited first by Clement of Alexandria in the 3rd century, but was rejected by Tertullian2 (c. 155/160–220) and Origen3 (c. 185–254). It is inconsistent with Luke’s quotation of “every male that opens the womb” (2:23). And if the Roman Catholic interpretation of Rev. 12:2 is correct and the woman is Mary, then there are further grounds for rejecting the idea that Mary was free from labour pains.

b) Virginitas post partum or perpetual virginity. This is not asserted before the Protoevangelium of James. Tertullian, despite his ascetic leanings, strongly opposed this doctrine as well.4 Roman Catholics justify this doctrine on the basis of Mary’s statement to Gabriel, “I know not a man.” (Lk. 1:34). They interpret this to mean, “I have taken a vow never to know a man.” This eisegesis was first suggested by Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335 – c. 394),5 but there are two difficulties here: first, the verb to know (γινώσκω ginōskō) is in the present active indicative, which should not be read as a future intention, and second, she was already betrothed to Joseph (v. 27). Mt. 1:25: “[Joseph] knew her not until she had borne a son” also rules out a sexless marriage—deleting the words after “not” would have been the correct way to teach this. Also, the very fact that God’s angel instructed Joseph to marry Mary implies a normal marital relationship, including the consummation so “the two become one flesh.”

The fact that Jesus’ brethren (ἀδελφοί adelphoi) were with Mary (Mt. 12:46–50) suggests that they were his half brothers, sons of Mary and Joseph (taught by Helvidius [4th century] and Protestants). The Eastern Orthodox view is that they were sons of Joseph by a previous marriage (first asserted in the 3rd Century and defended by Epiphanius in the 4th).6 The Roman Catholics view them as cousins (first asserted by Jerome6 (331–420)), although the word συγγενής (syngenēs, kinsman, cousin, used of Mary and Elizabeth in Lk. 1:36) could have been used to teach this, as could another Greek word ἀνεψιός (anepsios, Colossians 4:10). It is true that adelphoi may sometimes mean ‘cousins’, but the meaning ‘brothers’ follows “a basic, but often neglected hermeneutical principle. It is this: in the absence of compelling exegetical and theological considerations, we should avoid the rarer grammatical usages when the common ones make sense.”7

c) Immaculate conception—this refers not to Jesus’ conception but Mary’s, i.e. Mary was conceived in the normal human manner but free of the taint of original sin. This dogma was not defined by Rome until 1854. It is contradicted by the fact that Mary admitted that she needed a saviour (Lk. 1:46–47) and brought a sin offering to the temple (Lk. 2:21–24, cf. Lev. 12:6–8. See also Rom. 3:23). Smith’s Bible Dictionary points out that there is no trace of this doctrine in the Church Fathers in the first five centuries, and in fact that Mary was criticised by Tertullian, Origen, Basil the Great (329–379) and John Chrysostom (c. 350–407).8 Some of these criticisms of one who was “blessed among women” (Lk. 1:42) are very unfair, but the point is that these early Christians clearly did not believe that Mary was sinless. The Roman Catholic scholar Hilda Graef cites critical comments by these fathers, and also points out that Irenaeus taught that she was not free of human faults,9 and that the great Trinitarian Athanasius (c. 296–373), while not attributing actual sins to her, stated that “bad thoughts” came into her mind.10 Graef admits that it “… shows that the image of the spotless, perfect, immaculate Virgin had not yet emerged in the minds of the 4th Century fathers.”

2) Theological significance of the Virginal Conception

The New Testament scholar C.E.B. Cranfield11 makes four points, which I summarise as follows:

a) The Virginal Conception does not prove the Incarnation, nor does it say that it could not have happened any other way. But it does point to the union of God and man in Christ.

b) God made a new beginning of the course of the history of his creation by becoming part of it, coming to rescue fallen humanity from sin.

c) Jesus is truly human. The Second Person of the Trinity took on full human nature while remaining fully God.

d) “The Virginal Conception attests the fact that God’s redemption of His creation was by grace alone. … Our humanity, represented by Mary, does nothing more than just accept—and even that acceptance is God’s gracious gift.”

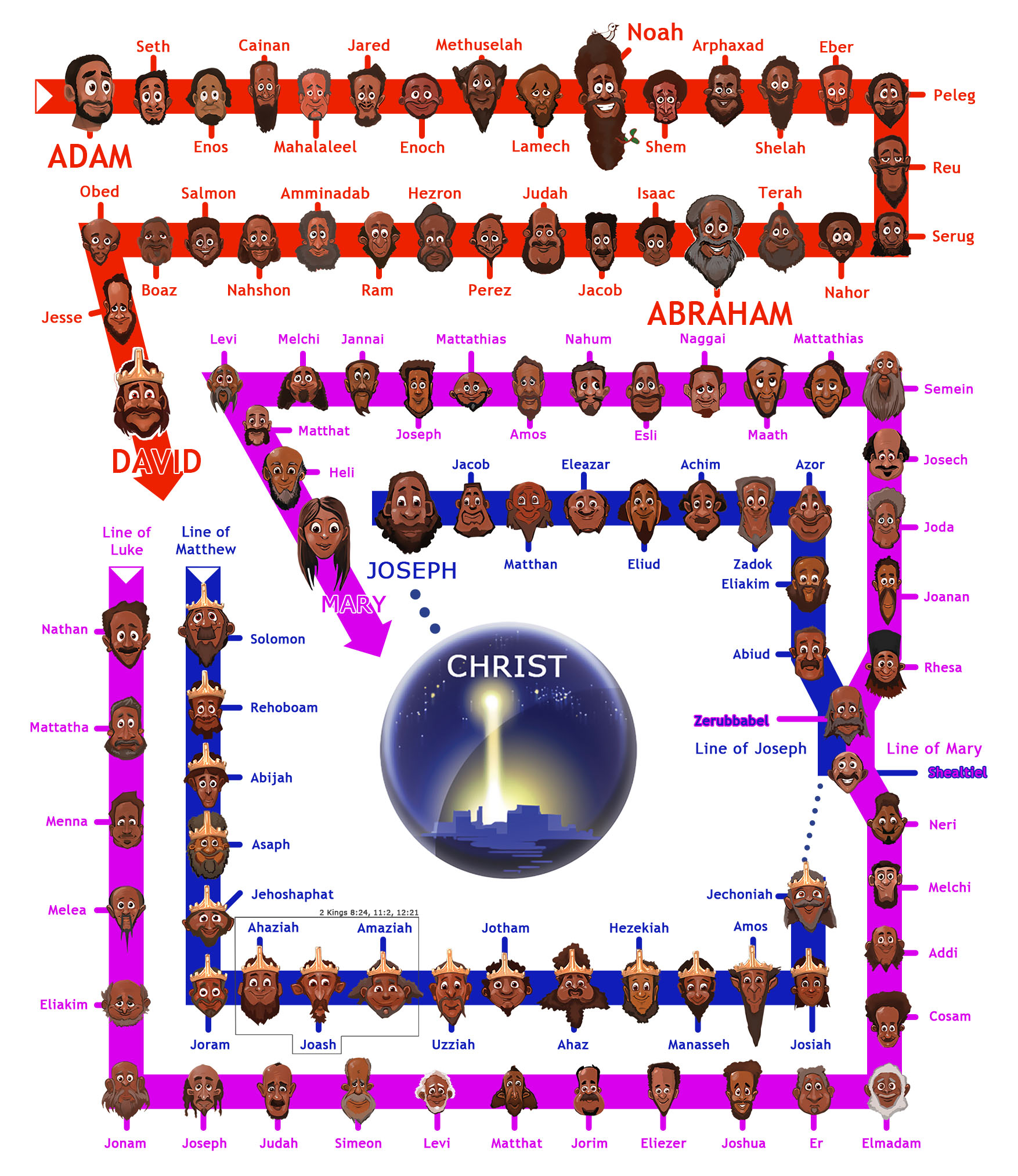

It was also necessary for Jesus to be physically descended from Mary, so He fulfilled the prophecies that He would be a descendant of Abraham, Jacob, Judah and David. Also, the Protevangelium of Gen. 3:15, regarded as Messianic by both early Christians and the Jewish Targums, refers to “the seed of the woman”. This is supported by Gal. 4:4, “God sent forth His Son, coming (genomenon) from a woman.” Most importantly, for Jesus to have died for our sins, Jesus, the “last Adam” (1 Cor. 15:45), had to share in our humanity (Heb. 2:14), so must have been our relative via common descent from the first Adam as Luke 3:38 says. In fact, seven centuries before His Incarnation, the Prophet Isaiah spoke of Him as literally the ‘Kinsman-Redeemer’, i.e. one who is related by blood to those he redeems (Isaiah 59:20, uses the same Hebrew word goel as used to describe Boaz in relation to Naomi in Ruth 2:20, 3:1–4:17). To answer the concern about original sin, the Holy Spirit overshadowed Mary (Luke 1:35), preventing any sin nature being transmitted.

3) Old Testament

a) Genesis 3:15:And I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will crush your head, and you will strike his heel. (NIV).

Many have interpreted the seed in this verse as the Messiah, including the Jewish Targums,12 hence the Talmudic expression “heels of the Messiah”.13 The early church writers called it the protevangelion, or first mention of the Gospel in the Bible. This verse hints at the Virginal Conception, as the Messiah is called the seed of the woman, contrary to the normal Biblical practice of naming the father rather than the mother of a child (cf. Gen. ch’s 5 and 11, 1 Chr. ch’s 1–9). The pronoun hû’ (he will crush your head (NIV), it shall bruise thy head (KJV)) can be translated “he”, “it” or “they”.14 A feminine pronoun (“she”) would have the consonants hî’. The Septuagint15 (LXX) translated the pronoun hû’ as αὐτός (autos), although the antecedent σπέρματος (spermatos) is grammatically neuter.14 This suggests that the LXX translators had a messianic understanding of the passage. The Latin Vulgate mistranslates hû’ as ipsa (“she”), which is followed by the Roman Catholic Douay-Rheims English translation of the Bible. Some Roman Catholics use this to teach that Mary would crush the serpent’s head. Their main justification is that some Hebrew manuscripts pointed the consonants16 of hû’ (הוא) to pronounce the word in the feminine way.17 However, basing dogma on rare vowel-pointing (which is uninspired anyway) is unwise.

In Gen. 4:1 in the original Hebrew, there is an interesting statement by Eve after the birth of Cain: literally “I have gotten a man: YHWH”, or “I have received a man, namely Jehovah”, as Martin Luther put it.18 The Hebrew Christian scholar, Dr Arnold G. Fruchtenbaum, supports this interpretation by pointing out that the word YHWH is preceded by the untranslated accusative particle ’et, which marks the object of the verb, in this case “gotten”.19 The Jerusalem Targum reads: “I have gotten a man: the angel of Jehovah”, while the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan says: I have gotten for a man the angel of Jehovah”.20

He believes that Eve’s actual statement shows that she understood that the seed would be both God and man, but she was grossly mistaken in believing that Cain was the seed in question.21 The Midrash Rabbah also cites Rabbi Akiba admitting that the Hebrew construction would seem to imply that Eve thought she was begetting YHWH, which created interpretive difficulties for them, so the translation “with the help of the LORD” is required22—as the NASB also renders it.

Hamilton defends the translation “I have acquired a man from Yahweh”,23 which is essentially the same as the KJV, and does not appear to support the above alternative translation “with the help of the LORD.”

b) Isaiah 7:1–17:24

1 When Ahaz son of Jotham, the son of Uzziah, was king of Judah, King Rezin of Aram and Pekah son of Remaliah king of Israel marched up to fight against Jerusalem, but they could not overpower it.

2 Now the house of David was told, “Aram has allied itself with Ephraim”; so the hearts of Ahaz and his people were shaken, as the trees of the forest are shaken by the wind.

3 Then the LORD said to Isaiah, “Go out, you and your son Shear-Jashub, to meet Ahaz at the end of the aqueduct of the Upper Pool, on the road to the Washerman’s Field.

4 Say to him, “Be careful, keep calm and don’t be afraid. Do not lose heart because of these two smouldering stubs of firewood—because of the fierce anger of Rezin and Aram and of the son of Remaliah.

5 Aram, Ephraim and Remaliah’s son have plotted your ruin, saying,

6 “Let us invade Judah; let us tear it apart and divide it among ourselves, and make the son of Tabeel king over it.”

7 Yet this is what the Sovereign LORD says:

“It will not take place, it will not happen,

8 for the head of Aram is Damascus, and the head of Damascus is only Rezin. Within sixty-five years Ephraim will be too shattered to be a people.

9 The head of Ephraim is Samaria, and the head of Samaria is only Remaliah’s son. If you do not stand firm in your faith, you will not stand at all.”

10 Again the LORD spoke to Ahaz,

11 “Ask the LORD your God for a sign, whether in the deepest depths or in the highest heights.”

12 But Ahaz said, “I will not ask; I will not put the LORD to the test.”

13 Then Isaiah said, “Hear now, you house of David! Is it not enough to try the patience of men? Will you try the patience of my God also?

14 Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel.

15 He will eat curds and honey when he knows enough to reject the wrong and choose the right.

16 But before the boy knows enough to reject the wrong and choose the right, the land of the two kings you dread will be laid waste.

17 The LORD will bring on you and on your people and on the house of your father a time unlike any since Ephraim broke away from Judah—he will bring the king of Assyria.”’ (NIV)

The context of this verse is that an alliance was threatening the idolatrous king Ahaz. Not only was he in danger, but the house of David was threatened with extinction. Therefore, Isaiah, addressing the house of David (as shown by the plural form of “you” in the original Hebrew of v.13), stated that a sign to them would be a virgin conceiving. To comfort Ahaz, Isaiah prophesied that before a boy (Isaiah’s son, Shear-Jashub who was present, v. 3) would reach the age of knowing right from wrong, the alliance would be destroyed (vv. 15–17). It is important to recognize that the passage contains a double reference, so there is a difference between the prophecies to Ahaz alone (indicated by the singular form of ‘you’ in the Hebrew—atah אתה) and the house of David as a whole (indicated by the plural form—lachem לכם). Some anti-Christians, starting with the medieval Jewish commentator David Kimhi,25 have failed to understand this and misinterpreted the child Immanuel as a sign to Ahaz, possibly Ahaz’s godly son Hezekiah.

The word for virgin here is עלמה (‘almāh). Some liberals26 and Orthodox Jews claim that the word really means ‘young woman’, and this is reflected in Bible translations such as the NEB, RSV, NRSV, and GNB. Such people fail to explain why a young woman’s bearing a son should be a sign—it happens all the time. The Septuagint translates ‘almāh as παρθένος (parthenos), the normal word for virgin.27 Later Jews, such as Trypho,28 Justin Martyr’s (c. 160) dialog opponent, and Rashi29 (11th cent.) have claimed that the Septuagint was wrong. Trypho claimed that ‘almah should have been translated neanis (young girl) rather than parthenos.30

However, even Rashi admitted that ‘almāh could mean ‘virgin’ in Song of Sol. 1:3 and 6:8. In the KJV, the word is translated ‘virgin’ in Gen. 24:43 (Rebekah before her marriage), ‘maid’ in Ex. 2:8 (Miriam as a girl) and Prov. 30:19, and ‘damsels’ in Ps. 68:25. These verses contain all the occurrences of ‘almāh in the OT, and in none can it be shown that a non-virgin is meant. In English, ‘maid’ and ‘maiden’ are often treated as synonyms for virgin (e.g. maiden voyage). Vine et al. note that the other word for virgin, בתולה (betûlāh), “emphasizes virility more than virginity (although it is used with both emphases, too).”31 betûlāh is qualified by a statement “neither had any man known her” in Gen. 24:16, and is used of a widow in Joel 1:8. Further evidence comes from clay tablets found in 1929 in Ugarit in Syria. Here, in Aramaic, a word similar to `almah is used of an unmarried woman, while on certain Aramaic incantation bowls, the Aramaic counterpart of betûlah is used of a married woman.32 The Encyclopedia Judaica, while criticising the translation of ‘almah in Is. 7:14 as ‘virgin’, also points out that btlt was used of the goddess Anath who had frenzied sex with Baal.33

4) Miracles

Liberal theologians often assert that modern scientific man cannot believe in the miracles widely accepted in a more primitive age. The following reasons have been advanced, but they are all fallacious:

- The ancients were more ignorant than the moderns. Back then, they were unscientific, and could believe in miracles like the virginal conception. Now that we are scientific and modern, we know how babies are conceived, so we should not believe those stories. Comment: the ancients knew very well how babies are made—needing both a man and a woman, although they did not know certain details about spermatozoa and ova. In fact, Joseph (Mt. 1:19) and Mary (Lk. 1:34) questioned the announcements of the Virginal Conception because they did know the facts of life, not because they did not! Similarly, ancients didn’t know about bacterial enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis of basic amino acids producing diaminoalkanes which strongly stimulate olfactory receptors, but they knew that a corpse will stink after a few days, and they informed Jesus of this before He raised Lazarus from the dead.

- The ancients were more gullible than the moderns. Comment: But, many ancients did not accept miracle claims, especially Christ’s Virginal Birth and Resurrection. Conversely, today, all the evolution-biased newspapers promote astrology (horoscopes), and consider the total acceptance of spontaneous generation among the evolutionary establishment despite being disproved by Louis Pasteur. This speaks volumes about modern man’s gullibility!

- Science has disproved miracles. Comment: the argument is that miracles violate scientific laws, and scientific laws have no exceptions, so miracles cannot occur. But we only know that scientific laws are universal if we know in advance that reports of miracles are false. In fact the argument is circular. The argument also has a false view of scientific laws—they are descriptive, not prescriptive. The laws do not cause or forbid anything any more than the outline of a map causes the shape of the coastline. But if God made the heavens and the earth, a Virginal Conception is no trouble for Him.

- The Bible miracle accounts are ‘myths’, not history. But this comes from the liberal dogma that miracles cannot occur, so all reports of them are ‘myths’. But most liberal theologians have no idea what a myth really is. C.S. Lewis, a professor of literature, knew full well what a myth was, and could find no trace of mythology in the NT. The NT had sober, on-the spot reporting, and interviews with eye-witness (Luke 1:1–4) and was about a historical figure everyone knew. We should look at all the legendary accretions in the later Gnostic so-called gospels to see what myths look like. E.g. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas has the child Jesus causing another child to become withered, another child to die, and that child’s parents blinded after they complained to Joseph.

- Believing in the Virginal Conception and other miracles commits one to belief in all sorts of superstitions. Comment: this is as logically fallacious as claiming that believing one politician’s promises commits one to believe all politicians’ promises. Also, the sober birth narratives in Matthew and Luke contrast with later legendary accretions in the Gnostic ‘gospels’.

5) Reliability of the birth narratives

a) The census: One of the many objections to Luke’s account is an alleged mistake concerning the census in Quirinius’ day (Lk. 2:2). The alleged problem is that Quirinius did not become governor until c. 7 AD according to Josephus, while Christ was born before Herod the Great died in 4 BC. However, the New Testament scholar N.T. Wright34 points out that πρῶτος (prōtos) not only means ‘first’, but when followed by the genitive can mean ‘before’ (cf. Jn. 1:15, 15:18). Therefore the census around the time of Christ’s birth was one which took place before Quirinius was governing Syria (Acts 5:37 proves that Luke was aware of the latter). Another possible solution is that Quirinius twice governed Syria, once around 7 BC and again around 7 AD, which is supported by certain inscriptions.35 Under this scenario, Luke’s use of prōtos refers to the first census in 7 BC, rather than the well-known one in 7 AD.

One should be sceptical of charges of error in Luke, for the archaeologist Sir William Ramsay stated: “Luke is a historian of the first rank; not merely are his statements of fact trustworthy … this author should be placed along with the very greatest of historians.”36

b) The genealogies: sceptics often allege that the genealogies of Christ in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke contradict each other and the Old Testament. There are three main areas of concern:

Matthew supposedly erred by leaving some names out. Here are the omissions:

Mt. 1:8 skips from Joram (=Jehoram) to Uzziah (=Azariah), but 1 Chronicles 3:11–12 adds the names Ahaziah, Joash and Amaziah:

11 Jehoram his son, Ahaziah his son, Joash his son,

12 Amaziah his son, Azariah his son, Jotham his son,The fact that Uzziah was another name for Azariah is shown by 2 Chronicles 26 , where Uzziah is also reported as the son of Amaziah and father of Jotham.

Mt. 1:11 skips from Josiah to Jeconiah (= Jehoiachin), but 2 Kings 23:34 and 2 Kings 24:6 show that Jehoiakim (name changed from Eliakim) was son of Josiah and father of Jeconiah.

But Matthew intentionally left a few names out, so it is not a mistake. It is also common in Scripture to use ‘son’ to refer to ‘descendant’, so Matthew was using perfectly acceptable language conventions of his day. In fact, the very first verse of Matthew’s Gospel says “… Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham.’, which is another clue that Matthew was deliberately not presenting an exhaustive genealogy. And Mt. 1:17 makes it clear that he is selecting 3 groups of 14, possibly because the Hebrew letters in the name David add up to 14, or because 14 = 2×7 (the number ‘seven’ often symbolizes completion, fulfilment or perfection in the Bible).

It is important to note that the clear indication that Matthew deliberately has gaps is no excuse for interpreters putting gaps in the genealogies of Genesis 5 and 11. In Genesis, the grammar is very different and explicitly teaches a strict chronology. See my article Biblical chronogenealogies.

- Luke 3:36 adds the name Cainan, which is missing from Genesis 11:12 (and 1 Chronicles 1:18). But the extra Cainan is probably one of the very few copyist’s errors in manuscripts available today. However, given that Genesis 11 is a strict chronology, and that those who copied the Hebrew Old Testament manuscripts were much more careful than those who copied Greek New Testament manuscripts, it’s most likely that Cainan was not in the original that Luke wrote. This is strongly supported by its absence in the earliest known manuscript of Luke, or in any commentaries by Jewish and Christian scholars before AD 220. For more information, see the discussion in Cainan: How do you explain the difference between Luke 3:36 and Genesis 11:12?

- Sceptics claim that the genealogies of Matthew and Luke contradict, because they supposedly give different fathers for Joseph, the husband of Mary.

However, Luke is tracing Mary’s line, showing that she was also a descendant of David, as implied in Luke 1:32. Conversely Matthew traced the legal line from Joseph to David, but this line was cursed because of Jeconiah (Jer. 22:17–30 ). This curse means that if Joseph had been Jesus’s biological father, then Jesus would not have been eligible to sit on King David’s throne. Here are some reasons that Luke should be understood as giving Mary’s line:- Luke’s nativity narrative mainly presents Mary’s perspective, while Matthew presented Joseph’s perspective. So readers of the original Greek would realize that the writers intended to present Mary’s and Joseph’s lines respectively.

- The reason Luke didn’t mention Mary explicitly is that rules for listing Jewish ancestry generally left out the mothers’ names.

- A clear pointer to the fact that the genealogy in Luke is Mary’s line is that the Greek text has a definite article before all the names except Joseph’s. Any Greek-speaker would have understood that Heli must have been the father of Joseph’s wife, because the lack of an article would mean that he would insert Joseph into the parenthesis (as was supposed) in Luke 3:23. The great New Testament Greek grammarian A.T. Robertson (1863–1934) writes: “‘The absence of the article puts the name outside of the genealogical series properly so-called.’—Godet. This would seem to indicate that Joseph belonged to the parenthesis, ‘as was supposed.’ It would read thus, ‘being son (as was supposed of Joseph) of Heli.’ Luke had already clearly stated the manner of Christ’s birth, so that no one would think he was son of Joseph. Jesus would thus be Heli’s grandson, an allowable meaning of ‘son’.”45 NB: the original Greek had no punctuation or even spaces between words. Indeed, the Jewish Talmud, no friend of Christianity, dating from the first few centuries AD, calls Mary the “daughter of Heli”, which could have come only from this understanding of what Luke meant.

6) Alleged silence of Mark, John and Paul

Some liberals, such as John Shelby Spong, Episcopalian Bishop of Newark in New Jersey,37 make much of Paul’s alleged silence to claim that he “stood as a witness to a normal human birth process for Jesus’. However, arguments from silence are nearly always inconclusive, and this is no exception. His alleged silence could mean that he saw no reason to correct the Virginal Conception stories circulating. Paul would certainly have been aware of such stories, as he was Luke’s companion (Acts 16:10–17, 20:5–21:18, 21:1–28:16), and cited Luke 10:7 in 1 Tim. 5:18. Paul does not directly discuss the birth process at all, so by Spong’s ‘logic’, Paul did not believe Jesus went through any birth process! [See also What’s Wrong With Bishop Spong?]

In fact, Paul does use language which implies acceptance of the Virginal Conception. He uses the general Greek verb γίνομαι (ginomai), not γεννάω (gennaō) since ginomai tends to associate the husband in Rom. 1:3, Phil. 2:7, and especially Gal. 4:4, “God sent forth His Son, coming (γενόμενον genomenon) from a woman.” By contrast, in 4:23 Ishmael “was born” (γεγέννηται gegennētai, from gennaō).38,39

Mark has no birth narrative, but he alone of the synoptists quotes objectors saying, “Is this not the carpenter, the son of Mary’ (Mk. 6:3, cf. Mt. 13:55 and Lk. 4:22).38,39 Addressing a Jew as his mother’s son was a great insult, implying fornication, so the objectors had probably heard the account of Christ’s conception, and were sceptical. It is also likely from this that Mark was also aware of the account.

John also has no birth narrative, but he is aware of rumors of Christ’s illegitimacy when he reports in 8:41 that the Jews declared: “We (emphatic pronoun and emphatic position) were not born of fornication.’38 This passage as well as Jn. 1:13 and 6:41 f. probably indicate that the evangelist believed in the Virginal Conception. 40

7) Spong’s midrash theory

In his recent book Born of a Woman attacking the Virginal Conception,37 Spong claims that the Virginal Conception accounts are examples of the literary genre of midrash (pp. 18, 20, 184). He (mis)understands midrash as follows:

Midrash represented efforts on the part of the rabbis to probe, tease, and dissect the sacred story [Old Testament] looking for hidden meanings, filling in blanks, and seeking clues to yet-to-be-revealed truth …

The gospels, far more than we have thought before, are examples of Christian midrash. In the gospels, the ancient Jewish story would be shaped, retold, interpreted, and even changed so as to throw proper light on the person of Jesus. There was nothing objective about the Gospel tradition. These were not biographies. They were books to inspire faith. To force these narratives into the straitjacket of literal historicity is to violate their intention, their method, and their truth … once you enter the midrash tradition, the imagination is free to roam and speculate.’

However, NT Wright34 points out that Spong does not know what midrash is. Wright shows that Spong ignores the leading current experts on midrash, such as Geza Vermes41 and Jacob Neusner42, since they leave no room for Spong’s distorted view. Spong also ignores Philip Alexander’s43 rebuttal of Michael Goulder’s use of the word ‘midrash’ which Spong relies on. Real midrash consisted of a commentary precisely on an actual biblical text, was tightly controlled and argued, and never included the invention of stories which were clearly seen as non-literal in intent.

8) Alleged pagan derivation

A common objection to the Virginal Conception is that there are supposed parallels in pagan mythology, e.g. the Medusa-slayer Perseus, born of the woman Danaë and sired by Zeus, the chief of the Greek pantheon. Zeus also fathered Herakles from Alkmene and Dionysus from Semele.39 Opponents of Christianity from Trypho and Celsus,44 who was refuted by Origen’s Contra Celsum (Against Celsus), till the present, have used this objection, but it has many flaws:

- This objection commits the genetic fallacy, the error of trying to disprove a belief by tracing it to its source. For example, Kekulé thought up the (correct) ring structure of the benzene molecule after a dream of a snake grasping its tail; chemists don’t need to worry about correct snake behaviour to analyse benzene! Similarly, the truth or falsity of Christianity is independent of the truth or falsity of its alleged parallels.

- Who derived from whom? Many of the legends like Mithra come after Christianity and were a reaction to it.

- The so-called parallels are not parallels at all! Perseus was not really virginally conceived at all, but was the result of sexual intercourse between the lecherous god Zeus and Danaë. Zeus had previously turned himself into a shower of gold to reach the imprisoned damsel. Zeus also fathered Herakles from Alkmene and Dionysus from Semele. Similarly for attempt to assert that the Resurrection of Christ was plagiarised—the death-rebirth-death cycles in paganism have nothing to do with the once and for all resurrection of Jesus, and the pagan gods didn’t die for our sins. And the Osiris legends have him remaining buried in the ground, while it’s a historical fact that Jesus’ tomb was found empty. Other alleged parallels are just as worthless, so it is pointless for sceptical scholars to multiply examples—zero times a hundred is still zero.

- Christ was a historical figure written about by people who knew him—quite different from the mythological parallels.

- The earliest Christians were Jews who abhorred paganism (see Acts 14), so would be the last people to derive Christianity from paganism.

- The existence of counterfeits does not disprove the real thing. No-one claims that real money can’t exist because there is counterfeit money. In fact, it is only valuable things that are counterfeited— who would want to counterfeit something worthless—so the existence of counterfeits is indirect evidence of the real thing. Of course, Satan wants to counterfeit the Word of God. We should know the real thing (God’s Word, and money too although far less important) so well that we can readily discern counterfeits.

Many of these points are covered in more detail in the article “Was the New Testament Influenced by Pagan Religions?’ by the scholar Dr Ronald Nash.

Conclusion

The Virginal conception of Christ is a vital doctrine of Scripture, and has withstood a wide variety of sceptical assaults.

References

- Hilda Graef, Mary: A History of Doctrine and Devotion 1:34, Sheed and Warde, NY, 1963. Return to text.

- Graef, Ref. 1, p. 43. Return to text.

- Graef, Ref. 1, p. 45. Return to text.

- Graef, Ref. 1, p. 34. Return to text.

- Graef, Ref. 1, p. 67. Return to text.

- Article on ‘Brethren of the Lord’, The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, IVP, Part 1, pp. 207–8, 1982. Return to text.

- S. Lewis Johnson; in: Stanley D. Toussaint and Charles H. Dyer, Essays in Honor of J. Dwight Pentecost, Moody Press, Chicago, p. 187, 1986. Johnson is actually defending the translation of kai as ‘and’ in Gal. 6:16, but his point still applies. Return to text.

- F. Meyrick in Smith’s Bible Dictionary; cited in: Harriet Beecher Stowe, Women of Sacred History, Portland House, NY, pp. 175–76, first published 1873, reprinted 1990. Return to text.

- Graef, Ref. 1, p. 40. Return to text.

- Graef, Ref. 1, p. 53. Return to text.

- C.E.B. Cranfield, “Some Reflections on the Subject of the Virgin Birth’, Scot. J. Theol. 41:177–89, 1988. This NT scholar rebuts many arguments against the Virginal Conception. Return to text.

- Aramaic paraphrases of the OT originating in the last few centuries BC, and committed to writing about AD 500. See F.F. Bruce, The Books and the Parchments, Fleming H. Revell Co., Westwood, p. 133, Rev. Ed. 1963. Return to text.

- A.G. Fruchtenbaum, Apologia 2(3):54–58, 1993. Return to text.

- Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1–17 (R.K. Harrison, Gen. Ed., New International Commentary on the Old Testament, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, 1990), p. 119. Return to text.

- The Septuagint was a Greek translation of the OT composed in ca. 250 BC, which was in widespread use by Jews outside Israel in NT times. Return to text.

- The original divinely-inspired autographs of the Hebrew OT contained only consonants, as does most modern Hebrew literature. A few centuries after Christ, scribes indicated what they thought were the correct vowels by certain marks around the consonants. A single dot under the consonant (hireq), in this case he ה, indicates the vowel sound in “bee’, and would make hû’ sound like hî’. Most Hebrew texts have a dot midway on the left (shureq) of the vav וּ, making it sound like u as in rule. The vowel points were not standardised until the 7th or 8th century by the Massoretes. See Gleason L. Archer, Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, Michigan p. 40, 1982. Return to text.

- R.E. Brown, K.P. Donfried, J.A. Fitzmyer and J. Reumann (eds.), Mary in the New Testament: A Collaborative Assessment by Protestant and Roman Catholic Scholars, Fortress Press/Paulist Press, Philadelphia, p. 29, 1978. Return to text.

- Hamilton, Ref. 14, p. 221. Return to text.

- A.G. Fruchtenbaum, Messianic Christology, Ariel Ministries, Tustin, CA, USA, pp. 15–16, 1998. Return to text.

- Cited in Fruchtenbaum, Ref. 19, p. 15. Return to text.

- See also Walter Kaiser, Jr., Toward an Old Testament Theology, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI, p. 37, 1978. Return to text.

- Cited in Fruchtenbaum, Ref. 19, p. 16. Return to text.

- Hamilton, Ref. 14, pp. 219 and 221. Return to text.

- See also Fruchtenbaum, Ref. 19, pp. 34–37. Return to text.

- ‘Immanuel’, Encyclopedia Judaica 8:1294–5, 1971 (Jerusalem: Keter). Return to text.

- J.S. Spong, Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism: A Bishop Rethinks the Meaning of Scripture, HarperSanFrancisco, 1991. Return to text.

- H.G. Liddell and R. Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Clarendon, Oxford, 1869; W.F. Arndt and F.W. Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, University of Chicago Press, p. 627, 2nd ed. 1971. Return to text.

- ‘Disputations and Polemics’, Encyclopedia Judaica 6:79–103. Return to text.

- A.G. Fruchtenbaum, Jesus was a Jew, Ariel Ministries, Tustin, CA, p. 32, 1981. Return to text.

- Graef, Ref. 1, p. 37. Return to text.

- W.E. Vine, M.F. Unger and W. White, Jr., Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words, Thomas Nelson, NY, 1985. Return to text.

- C.H. Gordon, J. Bible & Religion 21:106, April 1953; E.J. Young, ‘The Old Testament’, in C.F.H. Henry (ed.), Contemporary Evangelical Thought Channel Press, NY, 1957; both cited in W. Jackson, Biblical Studies in the Light of Archaeology Apologetics Press, Montgomery, AL, 1982. Return to text.

- ‘Virgin, Virginity’, Encyclopedia Judaica 16:159–160, 1971 (Jerusalem: Keter). Return to text.

- N.T. Wright, Who was Jesus, SPCK, Great Britain, p. 89, 1992. This book is an excellent critique by a New Testament scholar of the three recent anti-Christian books: 1) Barbara Thiering, Jesus the Man: A New Interpretation from the Dead Sea Scrolls; 2) A.N. Wilson, Jesus, Sinclair-Stevenson, London, 1992; 3) J.S. Spong, Born of a Woman: A Bishop Rethinks the Birth of Jesus, HarperSanFrancisco, 1992. Return to text.

- Gleason L. Archer, Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1982; W. Ramsay, Bearing of Recent Discoveries on the Trustworthiness of the New Testament, Baker, Grand Rapids, Michigan, pp. 223 ff, 1953. Return to text.

- W. Ramsay, Bearing of Recent Discoveries on the Trustworthiness of the New Testament, Baker, Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 222, 1953. Return to text.

- J.S. Spong, Born of a Woman: A Bishop Rethinks the Birth of Jesus, HarperSanFransisco, 1992. Return to text.

- Articles on ‘Virgin’ and ‘Virgin Birth’, The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, Part 3, pp. 1625–6. Return to text.

- Cranfield, Ref. 11. Return to text.

- C.K. Barrett, The Gospel According to John, London, pp. 164 and 348, 2nd ed. 1978. Return to text.

- G. Vermes, Post-Biblical Jewish Studies, E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1975. Return to text.

- J. Neusner, Midrash in Context: Essays in Formative Judaism, Scholars’ Press, Atlanta, 1988. Return to text.

- P.S. Alexander, ‘Midrash and the Gospels’ in C. M. Tuckett (ed.) Synoptic Studies, JSOT Press, Sheffield, 1984 and ‘Midrash’ in R.J. Coggins and J.L. Houlden (eds.), A Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation, SCM, London, 1990. Alexander deals directly with alleged midrash in Lk. 1–2 on p. 10. Return to text.

- J. Gresham Machen, The Virgin Birth of Christ, Harper & brothers, NY, Ch. 14, 2nd ed. 1932. This book by the great Princeton scholar is probably the most comprehensive on the subject. Return to text.

- A.T. Robertson, A Harmony of the Gospels, HarperSanFrancisco, NY, p. 261, 1922. The whole section pp. 259–262 has useful information about harmonization. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.