Feedback archive → Feedback 2021

A response to a long Sojourn advocate

We received many comments about our article How Long were the Israelites in Egypt. Most of those were answered in the commenting section below the article. Several, however, dealt with the claims of Dr. Douglas Petrovich, including one from Dr. Petrovich himself. It would not be fair to write a quick response to the details that are found in a long scholarly article, so we decided to pull the comment out and give it a long treatment in an article of its own. Petrovich’s 2019 paper Determining the Precise Length of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt will be discussed in depth below. Readers may want to consult the full paper, which is easy to find on the internet.1

Doug is a conservative Christian and a Bible scholar. He has written one article for our website. He and I appeared in the documentary Is Genesis History, and, even if we have never met in person, we travel in the same circles and have many friends in common. I write this, therefore, as a friend and fellow traveler for biblical inerrancy. Please keep in mind that in many areas, brethren can have differences of opinion on biblical issues which can be discussed openly, especially in academic circles. I encourage our readers to take this in the same spirit as my co-written 2019 article Iron sharpening iron: the MT-LXX debate as a case study of Christian disagreement. My goal is to clarify several issues as I critique his views on several others.

Here is Petrovich’s original comment:

I would encourage your readers to study my 2019 peer-reviewed article on the length of the sojourn in Egypt (not Canaan + Egypt), which demonstrates that the correct view is exactly 430 years. I deal in great detail with the textual variants involved, as this is the most extensive treatment of the issue yet published. Attempting to count generations and thereby falsify the correct chronological data is not utilizing proper hermeneutical methodology. Since links are not allowed, the article may be downloaded for free from my academia dot edu webpage. All the best, Dr. Douglas Petrovich Prof. of Biblical History and Exegesis, The Bible Seminary.

Hi Doug,

Thanks for the tip. I have indeed recently read your article. I wish I had done so before my article appeared on Creation.com, not because it would have changed my conclusions but because I would have then been able to head certain objections off at the pass.

Since I am trained as a scientist, with the added contribution of having done my undergraduate at an engineering school, certain ways of thinking and writing have been ingrained in my mind. Scientists do not deal with absolutes and engineers are always aware of ranges of possibilities. Also, I am a proponent of the ‘principle of multiple working hypotheses’. Instead of adamantly demanding adherence to one option when multiple valid options are available, my method is to weigh the evidence in favor of each and then assign boundary conditions (e.g., my article The biblical minimum and maximum age of the earth). Even if I have a preferred opinion, I try to keep an open mind when discussing these things with others. I sometimes fail to meet my own standards, but this is my goal.

This way of thinking is strange to many people. Very often, someone will comment, “So, you believe X”, as if X was some ultimate conclusion to be drawn from my attempt at a balanced analysis. Instead, I might prefer X, or I might feel that the preponderance of evidence points toward X, but this does not mean I “believe” X. Don’t get me wrong; there are places where absolute conclusions can be drawn, but there are other places where only strong arguments can be made, and still other places where ambiguity reigns. The key to good scholarship is being able to tell the difference.

Thus, it was strange to me to read certain phrases in your paper. For example: “incontrovertible evidence”, “completely incongruous”, “exclusively supporting”, “undoubtably”, “proven”, “uniformly attest”, “argues overwhelmingly”, “so overwhelmingly one-sided”, “the correct synchronism”, “totally implausible”, and “precisely harmonizes”. Such phraseology is foreign to my scientific ear, and one does not usually hear academics speak in such dogmatic terms. There is too much preference for your personal view and, thus, too much dismissiveness of other views, especially considering the raging controversy surrounding this issue.2 Your wording also contradicts your statement that, “ … many scholars are comfortable counting 215 years from the time that Jacob and his sons entered Egypt until the deliverance under Moses.” If many scholars disagree with you, how can you be so emphatic that you are correct?

I happen to agree with you on the date of the Exodus and your putative identification of the Pharaoh of the Exodus, so there is no need to discuss Rohl’s revised chronology, for which I see no support. However, the 215-year difference in the length of the Sojourn would affect our identification of the Pharaoh of Joseph and the historical period in which the Israelites were in Egypt. I am not going to comment on your paleographical evidence for the long Sojourn, for it has been some time since I read your work on the subject and I did not originally do so with this controversy in mind. Yet, there are good logical, and biblical reasons for Joseph arriving later, for example during the Hyksos period, which we outlined in our Tour Egypt book (see box below) and in Bates’ article Egyptian chronology and the Bible—framing the issues.

Missing generations?

You wrote,

“Attempting to count generations and thereby falsify the correct chronological data is not utilizing proper hermeneutical methodology.”

My first response is, “Excuse me?” We were only doing what you said to do in your paper. That is,

“These declarations of Scripture become the primary evidence for determining not only the date of the exodus but also the length of the Egyptian sojourn.”

Our paper is examining what you purport is the primary evidence. The genealogical data are evidence. One cannot simply wave them away. Moreover, I cannot see how anyone can say that a detailed examination of these data are not “proper hermeneutical methodology.” We were not “trying to falsify” anything. Instead, we were looking at an area that many have skipped over in the past. Chronologies are very important in Scripture because they are there to show us that the Bible records real history with real people and the events surrounding them. If we are not to take them as an accurate record then it makes no sense why God tells us of the ages of the patriarchs, when they had children, and how long each successive generation lived.

Now that the detailed genealogy has been laid out, a discussion can ensue. The biblical data are clear; there is no hint in the text that the people listed in our table are not parent-child relationships, so the burden of proof is now on the shoulders of the long Sojourn supporters to show why there necessarily are missing generations. This is ultimately an argument from silence.3 If they fail, the challenge stands. It really is that simple.

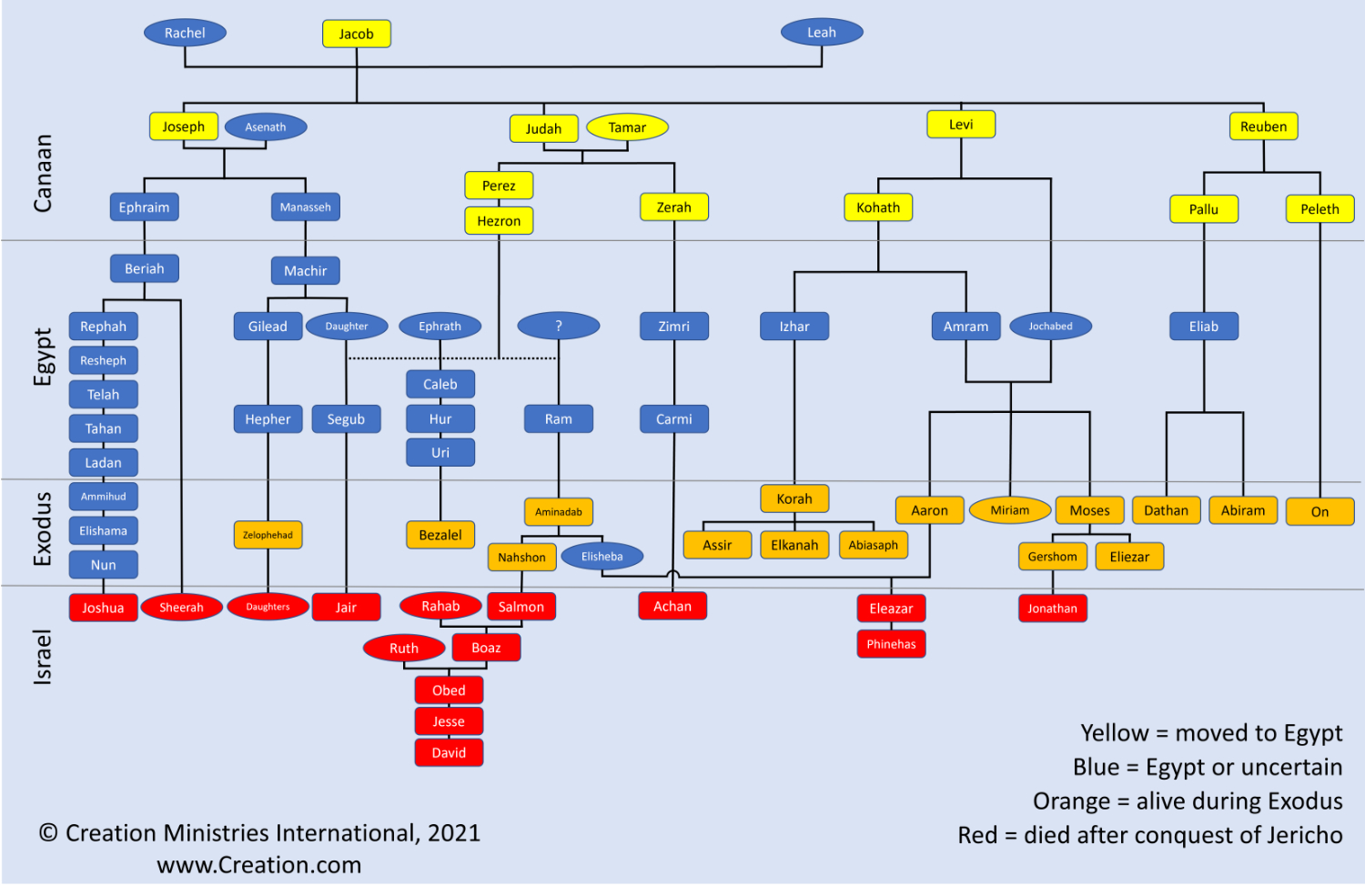

To my mind, this was the first analysis of the detailed genealogical intertwining among the many family trees that span the Sojourn and Exodus. Appeals to “missing generations” are common, but somebody will have to come up with a workable scenario that explains how to make that family tree with no contradictions or confusions when there are supposedly missing generations. Many people also claim skipping generations is common in biblical genealogy, but I have yet to see anyone demonstrate that this was “common”. Luke 3 vs Matthew 1 is often cited. This would be a good example if Matthew is trying to show an actual genealogy and not, like J. Gresham Machen claimed,4 a royal king list that would have jumped around among the descendants of David when certain men died with no heir. But Matthew’s list has a different style and purpose than the family tree of the Israelites in Egypt, which is not contained in one single place. The family tree we showed is not a ‘genealogy’, per se, but a curated data set from which a genealogy can be constructed. The fact that the data are dispersed in Scripture and yet can be assembled into a coherent tree structure with no internal conflicts is strong evidence that there are no missing generations.

Is the genealogy primary or secondary evidence?

You also wrote, “Testimony obtained through archaeology, epigraphy, and other subfields of ancient history thus becomes secondary evidence, which should be consulted only after proper dates are established and accurate synchronisms are achieved.” Therefore, your evidence for ancient Hebrew writing (e.g., epigraphy) at earlier time periods than the short Sojourn allows is, by definition, secondary evidence. We cannot pick and choose among the primary and secondary sources of evidence. Our analysis attempts to add a significant new area to the debate, and it is solely a textual argument. By your own words it must have precedence over outside evidence, including your own.

Which text?

“The time that the people of Israel lived in Egypt and in the land of Canaan was 430 years. At the end of 430 years, on that very day, all the hosts of the Lord went out from the land of Egypt.” Exodus 12:40–41

To other readers: In the biblical quote above, the words in red are found in the Greek Septuagint (or LXX) but not the Hebrew Masoretic (MT). The Samaritan Pentateuch (SP) also includes the addition, but the information about Egypt and Canaan are reversed. These represent the three main versions of the text of Exodus. The LXX is a Greek translation that was made in Alexandria, Egypt in the 3rd century BC. The SP is written in a Hasmonean (intertestamental period) Hebrew script. It only contains the first five books of the Bible and is known for the way is deliberately harmonizes different passages and for making obvious editorial changes (i.e., they have the Temple on Mt Gerizim, Samaria, instead of Mt Zion, in Jerusalem). The MT is the basis for essentially all modern translations (KJV, ESV, RSV, NIV, etc.). See Textual traditions and biblical chronology for more information.

Regarding the textual variants of Exodus 12:40, we can safely discount the witness of the Samaritan Pentateuch for, in your own words, “ … the reading in the LXX almost certainly led to the reading in the Samaritan Pentateuch.” You also wrote,

“While the LXX undoubtedly was translated from a Hebrew text of the Torah, there is no way to demonstrate that its underlying Hebrew text reflects an original text of the Torah, or that its quality is inherently superior to the earliest exemplars that underlie the readings in the MT.”

I would like to add that, since there is no evidence for the existence of the variant dates in Genesis 5 and 11 in any Hebrew (non-SP) source, we cannot know if the Greek LXX contains an original reading or if the translators made editorial changes designed to reflect opinions garnered from or informed by sources outside the text. The additional information included in Exodus 12:40 in the LXX, therefore, might not exist in any prior text and might simply reflect the struggles of the scholars to clarify a seeming problem with the timing of events. Their additions make it clear they believed the Sojourn began with the call of Abraham. This is an important point because the LXX was written several centuries BC and so they did not have access to Paul’s statement in Galatians (see later). On the other hand, if the translators were not being completely faithful to the text, the LXX chronology should be treated with more suspicion than many do today. Sanders and I threw down the gauntlet on the LXX vs MT debate for the genesis 5 and 11 chronogenealogies in our 2018 article Is the Septuagint a superior text for the Genesis genealogies? and we have yet to see someone seriously address our main challenges.

Textual variants

I want to bring out an important consideration about the use of words. To claim a textual variant exists between the MT and the LXX or SP is not the same as claiming a textual variant exists among, for example, manuscripts of the Greek New Testament. Why? First, because the former deals with translation differences and the latter deals more with scribal differences (most of which amount to nothing more than simple spelling errors or the placement of the “moveable nu”5). The SP is clearly a recension,6 which casts suspicion on how well it reflects the source text on which it is based. The LXX is a translation, yet the proto-LXX Hebrew behind it is only hypothetical. There is no evidence for its existence, so LXX advocates cannot clearly demonstrate that the LXX is not highly editorialized (i.e., a Greek recension of the Hebrew text). In the same way that the King James translators added words to the text to try and clear up seeming discrepancies (e.g., “the brother of” controversy in 2 Samuel 21:19), what is to say that the LXX translators did not add their own editorial bias, perhaps even to significant portions of the text? Calling the MT, LXX, and SP differences “textual variants” is a stretch. At least, scholars should come up with better phraseology to indicate the degree of difference. It is not small.

If the LXX translators, Josephus, and, perhaps, Paul, all thought the 430-year clock started with Abraham, we must ask why they thought the way they did. Josephus and Paul could have been informed by the LXX. Paul, at least, could read Hebrew and would have been familiar with an MT-like reading, yet he still chose wording that easily lends one to believe he thought the 430-year clock started with Abraham.

I thought you were an LXX advocate. That is, in Beyond Is Genesis History, volume 3 you make statements about the longer LXX chronology and how you believe it better fits with secular archaeology.7 At CMI, we don’t ‘fit’ secular history into Scripture. Rather, being faithful to the Word first and foremost, we try to analyze historical evidence within the lens of Scripture. Given your pro LXX statement, thus, I find it incongruous that you disagree with the LXX reading in Exodus 20. No doubt, you will reply that you are trying to be faithful to the original text, not the LXX translation. Yet, how can one know, and how can we justify accepting one (the Genesis 5 and 11 chronogenealogies) while rejecting the other (the statement in Exodus 12) when the exact same textual evidence in Hebrew (i.e., essentially none) exists for both? You hint that there is an article forthcoming that demonstrates how the LXX and SP contain the original numbering scheme of Genesis 5 and 11. I cannot comment in detail, but I am not at all confident that you will be able to make that case.

Are the Hebrews or the Israelites included in Exodus 12:40?

You attempted to make the argument that only the word Israelite (i.e., ‘descendant of Jacob’) is used in Exodus 12:40 and so this verse cannot be talking about Abraham (‘the Hebrew’), Isaac, or even Jacob. Yet, it would be improper to use the word Hebrew here, for only a subset of the Hebrews (i.e., the Israelites) came out of Egypt. In fact, to say it was the Hebrews who left Egypt would be nonsensical, for the descendants of Ishmael, Esau, and Abraham’s sons through Keturah were all technically Hebrews and they, of course, did not participate in the Exodus. Exodus is explicitly correct here, and it could not be any other way.

396 years?

Immediately after this, you discuss the LXX and SP readings and how these conflict with a short Sojourn. However, you are jumbling together multiple views, to the point where the argument makes little sense:

“Any interpretation of the verses in Genesis that places the starting point before Jacob had children is inconsistent with the text.”

This, of course, is in your opinion only and it has no hermeneutical support.

“For those who maintain that the LXX and Samaritan Pentateuch are correct in adding Canaan to the place of sojourning, the time that Jacob and his family spent in Canaan before entering Egypt must be included in the 430 years.”

Yes, exactly. This has always been part of the short Sojourn model, so it is irrelevant. But then you set up a false dichotomy:

“Adding that time, which equals about 34 years (Steinmann 2011, 76), still leaves 396 years for the Egyptian sojourn, an unacceptable length for short-sojourn advocates.”

Yes, of course, but nobody argues this. Instead of starting the clock with Jacob in Canaan, the short Sojourn position is that the clock starts with the promise made to Abraham two centuries earlier.

“For this reason, the Egypt-plus-Canaan sojourn view is necessarily impossible unless its proponents desire to alter the length of the Egyptian sojourn from 215 to 396 years, which is highly unlikely for the chronological revisionists because their entire scheme would be dashed if required to add 163 years to the Egyptian sojourn. Even if short-sojourn advocates can accept an Egyptian sojourn long beyond 215 years, the responsibility falls on them to identify an extraordinary event during the lifetime of Jacob’s sons or progeny that inaugurated the 430 years of Exodus 12:40.”

You seem to be addressing Egyptologist David Rohl’s revised chronology, as if all short Sojourn advocates agree with Rohl. This is certainly not the case, and definitely not true of the staff at CMI. And, no, there is no need to identify an “extraordinary” event in Jacob’s lineage to start the clock because it had already been ticking for 200 years, according to the short Sojourn view.

Statements from Paul

You discussed Paul’s statement to the synagogue at Pisidian Antioch:

“The God of this people Israel chose our fathers and made the people great during their stay in the land of Egypt, and with uplifted arm he led them out of it. And for about forty years he put up with them in the wilderness. And after destroying seven nations in the land of Canaan, he gave them their land as an inheritance. All this took about 450 years. And after that he gave them judges until Samuel the prophet.” (Acts 13:17–20)

You wrote that the

“ … three different events total about 450 years when added together: the sojourn, the forty years of wandering in the desert, and the conquest of the seven nations—which culminated in the parceling out of the promised land to the Israelite tribes. This period of roughly 450 years fits the long-sojourn view perfectly but effectually cripples the short-sojourn view.”

I cannot see how it “cripples” the short Sojourn view when you failed to realize that the clock may have started ticking when God “chose” Abraham, one of the “fathers”. There is nothing in the text to suggest God chose these “fathers” after they got to Egypt, after all. God chose the “fathers”, starting with Abraham, according to the short Sojourn view. Then, about 450 years later, they finally received the land as their inheritance.

Does the 430 years in Galatians 3:17 start with Abraham or Jacob?

“Now the promises were made to Abraham and to his offspring. It does not say, “And to offsprings,” referring to many, but referring to one, ‘And to your offspring,’ who is Christ. This is what I mean: the law, which came 430 years afterward … ” (Galatians 3:16-17)

The Hebrew text certainly uses the singular ‘offspring’, and here Paul directly claims this was Jesus. Does, as you claim, the clock start ticking with the final promise made by God (i.e., to Jacob as he was travelling to Egypt) or with the initial promise made to Abraham? If it starts ticking with Jacob, the 2nd-generation offspring of Abraham, what, then, do we do about Jesus? You then go on to argue that:

“The context of Galatians 3:17 makes it known that Paul was speaking of this very event that Jacob had experienced.”

Despite the many words used to support this idea, you are far from demonstrating this to be true. Regarding the short Sojourn position, you state:

“For them [i.e., short Sojourn advocates], this confirmation of the Abrahamic covenant could apply only to Abraham in this verse, not to Isaac or Jacob, because it was initiated only with Abram.”

There are multiple issues with this. First, it is not that the confirmation can “only” apply to Abraham but that a natural reading of the text seems to indicate that it does. There might be some nuanced way of explaining it otherwise, but such an explanation does not leap from the page. Second, is it not true that the covenant was initiated “only” with Abram?

“This leads to an important point: there is no reference whatsoever in Galatians 3:15–18 to Abram’s relocation to Canaan, Jacob’s relocation to Egypt, Israel’s sojourn in Egypt, or Israel’s exodus from Egypt.”

An “important point” for whom? According to short Sojourn advocates, the reason for this is that the clock started ticking at the beginning of your list of events. In this view, the other items were not mentioned because Paul’s intent was to span the promise made to Abraham and the giving of the Law: 430 years. You then say:

“Neither can Abraham’s receiving of the promise be identified as the nearest referent. Instead, the nearest referent in the main argument is the statement that the promises were spoken by God to Abraham’s seed.”

No, Paul specifically says that Abraham’s seed is Christ. Thus, the nearest referent to the 430 years is indeed Abraham.

Four generations or four indeterminate spans of time?

“Then the Lord said to Abram, ‘Know for certain that your offspring will be sojourners in a land that is not theirs and will be servants there, and they will be afflicted for four hundred years. But I will bring judgment on the nation that they serve, and afterward they shall come out with great possessions. As for you, you shall go to your fathers in peace; you shall be buried in a good old age. And they shall come back here in the fourth generation, for the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet complete.’” (Genesis 15:14–16)

The use of “400” here could be an approximation, so it is not an argument either way. Also, the argument does not hinge on this “400”, since the “430” is given to us in Exodus 12:40. I do not wish to dismiss it too quickly, however, and we provided in our article (as others have done before) a rational way to correlate the “400” and “430” year spans with no conflict.

But you then attempt to make the case that the word ‘generations’ (dor) might be translated incorrectly. You suggest the translation should be ‘four periods of time’, which, as you show, might have some support. Yet, even if this were the case, the question of where the breaks between each period should be located is still on the table. You want the spans to equal 100-year intervals, which bring us back to the “400” above. That’s fine, but you have yet to demonstrate why the peg has to be with Jacob and not Abraham. You also only provide three timespans:

“In other words, the 400-year period would consist of three events with no predictive indication of their individual durations: (1) the Israelites’ living as strangers in a foreign land, (2) the Israelites’ serving these foreigners, and (3) the afflictions that the Israelites would experience at the foreigners’ hands.”

Why could the four timespans not be: (1) Abraham in Canaan, (2) Joseph in Egypt, (3) persecution, (4) Exodus? If the Israelites are in Egypt for about 215 years, these four timespans also equate to 430 years.

Conclusions

In the end, I do not believe you have fully addressed the evidence supporting a short Sojourn. Neither have you made an ironclad case for the long Sojourn. The genealogical data are what they are. There is not a hint of missing generations, until, that is, one tries to apply a longer timeframe than they allow for. I understand there are many additional factors at play here, specifically issues with archaeology. One cannot glibly accept the short Sojourn or reject the long Sojourn. Either position has strengths and weaknesses. Yet, I still maintain that the most natural reading of the text (including Paul’s statements and the family tree) indicates a short Sojourn. The most problematic reference is in Exodus 20. Yet, the ancient textual ‘variants’ found in the LXX and SP support the short Sojourn, as do many ancient writers. The debate is not going to go away, but we need not jettison the short Sojourn just yet.

A non-Egyptian pharaoh?

By Gary Bates and Robert Carter

The question of How long the Hebrews were in Egypt (i.e., a ‘long’ Sojourn of 430 years or a ‘short’ Sojourn of ~215 years) is important as it can help us understand the period in which Joseph was imprisoned and ultimately became vizier over Egypt.

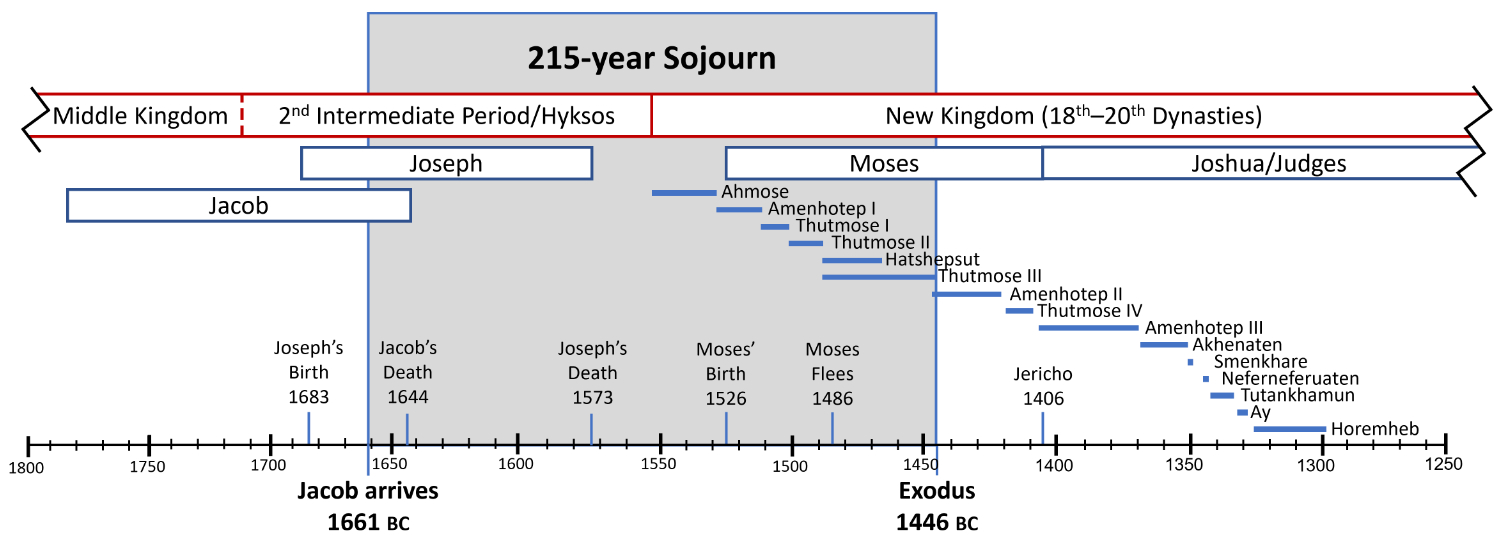

Most evangelical scholars generally believe the building of the Temple (the fourth year of Solomon’s reign) began in 966 BC. Going backwards 480 years (1 Kings 6:1) would mean the Exodus occurred in 1446 BC. Going back another 215 years, the short Sojourn would place Joseph in the midst of the 2nd Intermediate Period (2IP) of Egyptian history. This is the time when the mysterious Hyksos peoples had taken over. These were a Semitic people who had slowly moved in from the east. Eventually, during a confusing time in Egyptian history, they took over a large portion of the country. Six consecutive Hyksos pharaohs are thought to have ruled. There is uncertainty as to when the 2IP began and how long it lasted. We do know they ruled from the northern Delta region, where the Israelites were given land. Their time ended when the brothers Ahmose and Khamose attacked from the south and reclaimed the land for the Egyptians. Ahmose became the first Pharaoh of the New Kingdom’s 18th Dynasty.

A long Sojourn would place Joseph earlier, in the Middle Kingdom, around the year 1876 BC, possibly during the reign of the native Egyptian pharaoh, Sesostris II. Yet, this depends very much on the length of the 2IP.

Textual clues might help us determine whether the pharaoh was Egyptian or not. There is good Scriptural evidence to suggest that Joseph was interacting with a non-native/non-Egyptian pharaoh, which fits the Hyksos period and a short, 215-year Sojourn. The following is adapted from our Tour Egypt book, which we would highly encourage everyone to read in its entirety.

From Tour Egypt with Creation Ministries International

[Emphasis ours] Jacob and Joseph would thus be located within the Second Intermediate Period—a time when northern Egypt (which incorporates the land of Goshen) was ruled by non-Egyptian pharaohs—a Semitic group known as the Hyksos (Egyptian heqa khasut, or ‘rulers of foreign lands’). Scripture indicates that Joseph found favour under the local ruler, who is alternately called a pharaoh and a king. But consider native Egyptian culture: they believed that their ‘blessed land’ was due to the favour bestowed upon them by their multitude of gods. Students of ancient Egypt understand how native Egyptians viewed foreigners. They were an underclass.

Was Joseph’s Pharaoh non-Egyptian?

This has rarely been discussed, but in context, it does not seem credible that Joseph rose to power under the rule of a native Egyptian pharaoh. By promoting Joseph as vizier over the whole country, pharaoh was legitimizing Joseph’s God. Why couldn’t one of Egypt’s many gods interpret the dream? If this was an Egyptian pharaoh, to appoint a foreigner to rule over the land would have been a huge assault on the priestly religious system and culture going back in an unbroken chain for close to a thousand years. To undermine the Egyptian gods in such a way would have been sacrilegious, particularly when the whole political and religious system was based upon receiving favour from the gods and the god’s divine representative (Pharaoh). Scripture also provides some clues about this. For example, Genesis 39:1–2 says:

“Now Joseph had been brought down to Egypt, and Potiphar, an officer of Pharaoh, the captain of the guard, an Egyptian, had bought him from the Ishmaelites who had brought him down there. The Lord was with Joseph, and he became a successful man, and he was in the house of his Egyptian master.”

It seems to specifically highlight that Potiphar is an Egyptian working under the pharaoh. Keep in mind that the Hyksos adopted Egyptian ways, like many subsequent invaders after them (i.e., the Greek Ptolemies). They did not abandon the structural and cultural norms that were in place. Instead, they used them to their advantage. Potiphar is called an Egyptian again in verse 5:

“From the time that he made him overseer in his house and over all that he had, the Lord blessed the Egyptian’s house for Joseph’s sake; the blessing of the Lord was on all that he had, in house and field.”

If Pharaoh was also an Egyptian, why is Scripture singling out Potiphar in such a way? On four occasions Scripture distinctly references Potiphar as an Egyptian, but not Pharaoh. After Joseph had interpreted Pharaoh’s dream and advised him to store up grain, the Bible says:

“And Pharaoh said to his servants, ‘Can we find a man like this, in whom is the Spirit of God?’ Then Pharaoh said to Joseph, ‘Since God has shown you all this, there is none so discerning and wise as you are. You shall be over my house, and all my people shall order themselves as you command. Only as regards the throne will I be greater than you’” (Gen: 41:38–40).

What is notable is Pharaoh’s acknowledgment of a single God, not multiple gods. Scripture capitalizes ‘God’ here, whereas later it references the Egyptian ‘gods’ as lower case ‘g’. Pharaoh would have credited his own gods for the interpretation of the dream if he was an Egyptian. And Joseph certainly credited his God for the interpretation so there was no misunderstanding. Pharaoh acknowledges this and clearly shows deference to Joseph’s God. If Pharaoh was an Egyptian, this would be unthinkable for the reasons mentioned earlier. However, if Pharaoh was Semitic, it is at least possible that he would be more accepting of Joseph’s God.

Later, we see Jacob/Israel’s sons encountering their brother Joseph in Egypt. They had travelled there due to famine in their own country. By now, Joseph is vizier over the whole land of Egypt, but at this stage Joseph has not revealed his identity to his brothers, who had previously sold him into slavery. He orders that they be fed:

“They served him [Joseph] by himself, and them [the brothers] by themselves, and the Egyptians who ate with him by themselves, because the Egyptians could not eat with the Hebrews, for that is an abomination to the Egyptians” (Genesis 43.32).

If the Hebrews were an abomination to the Egyptians, why would an Egyptian king elevate Joseph in such a way? And why would the Egyptians continue the practice of disassociating themselves from the Hebrews? Perhaps Potiphar and Joseph’s servants were Egyptian, unlike the Hyksos rulers, who must have employed many native Egyptians in their service. Compare this to Daniel 1, where the four Jewish servants of the pagan Babylonians refuse to eat the food provided for them. The two parties worked out a compromise mutually acceptable to both sides and they got along fine after that. Genesis 46 adds more to the argument that this was the Hyksos period. Joseph’s brothers have returned to Egypt with their father Jacob. We read:

“Joseph said to his brothers and to his father’s household, ‘I will go up and tell Pharaoh and will say to him, “My brothers and my father’s household, who were in the land of Canaan, have come to me. And the men are shepherds, for they have been keepers of livestock, and they have brought their flocks and their herds and all that they have.” When Pharaoh calls you and says, “What is your occupation?” you shall say, “Your servants have been keepers of livestock from our youth even until now, both we and our fathers,” in order that you may dwell in the land of Goshen, for every shepherd is an abomination to the Egyptians’” (emphasis ours).

Why would Joseph be telling his family to identify themselves as something detestable in the eyes of Pharaoh if Joseph wanted them to be favoured? If Pharaoh was a native Egyptian, this passage makes little sense. Some might argue that Joseph told them this so they would be given an allotment of land far away from the Egyptians. But Genesis 47:11 says,

“Then Joseph settled his father and his brothers and gave them a possession in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land.”

Would an Egyptian king have sanctioned the giving of any portion of the ‘blessed land’, let alone the “best” portion, to sheep herding foreigners whom they thought were an abomination? Placing Joseph in the context of the Semitic Hyksos dynasty, centered as it was in the Nile delta region (near the land of Goshen), makes much more sense. Although he may have misinterpreted the term Hyksos, Manetho identified the Hyksos as ‘shepherd kings’ (a claim later repeated by Josephus). His claim may provide some historical context as to why they were friendly to other sheepherders like the Hebrews, as we have already seen. Scripture clearly indicates that shepherds were not an abomination to the pharaoh of Joseph’s time. This pharaoh says to Joseph:

“The land of Egypt is before you. Settle your father and your brothers in the best of the land. Let them settle in the land of Goshen, and if you know any able men among them, put them in charge of my livestock” (emphasis ours).

Summary of evidence that supports a Hyksos pharaoh in Joseph’s time:

- The timing is perfect for a short Sojourn.

- A Hyksos pharaoh would have been Semitic, thus more likely to be friendly toward the Israelites. The Egyptians considered all outsiders to be non-human.

- Potiphar is consistently and distinctly identified as ‘the Egyptian’.

- Joseph rode a chariot (Genesis 41:43). The first mention of chariot use in warfare was by Ahmose, when he conquered the Hyksos, but it generally believed that the Hyksos were the ones who introduced the ‘battle’ chariot to Egypt.8 Chariots were not in use widely during the Middle Kingdom.

- Pharaoh gave them pick of the best land. Foreigners were considered to be an underclass and the land was sacred to the Egyptians. Thus, it would be entirely unlikely for an Egyptian pharaoh to give away ‘the best of the land’. But a foreign ruler looking to shore up his support base and reduce the power of the native population would be expected to act as this pharaoh did.

- Pharaoh singled out Israel’s God. Again, this is entirely strange for an Egyptian pharaoh, who was seen as an embodiment of the Egyptian gods.

- Pharaoh gave them land in the NE area of Egypt, in other words, using the Israelites as a buffer against invaders from the east (where the Hyksos initially came from). This also indicates there were more than just 70 Israelites, by the way, or pharaoh would have simply told them to move into some neighborhood in some small town.

- A “pharaoh who did not know Joseph” arose (Ex. 1:8). This could easily correspond to the re-conquest of Egypt by Amhose. Fear and resentment against all easterners could easily explain why the Israelites were put into bondage. Also, the “mixed multitude” that went with the Israelites when they left Egypt could easily have contained other mistreated non-Egyptians, like the remains of the subjugated Hyksos people.

References and notes

- Petrovitch, D. N., Determining the Precise Length of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt, Near Eastern Archaeological Society Bulletin, 64:21–41, 2019; academia.edu/40790408/. Return to text.

- See, for example, the letter to the editor and replies from the authors in J. Creation 21(3):62–66, 2007. The correspondent is complaining about two recent article that supported a short Sojourn view: Viccary, M., Biblical chronology—our times are in His hands, J. Creation 21(1):62–66, 2007 and Austin, D., Chronology of the 430 years of Exodus 12:40, J. Creation 21(1):67–68, 2007. Return to text.

- Arguments from silence are common, but they are generally invalid. On the one hand, it is impossible to disprove an argument from silence, but on the other hand there is, by definition, no supporting evidence for it. Part of the drive toward strict appeals to naturalism during the modern scientific revolution was due to the many arguments from silence made during the medieval and earlier periods (after all, one cannot disprove how many angels can dance on the head of a pin). They went too far in that many scientists now reject any sense of the miraculous even though naturalism has a terrible track record of explaining origins. Return to text.

- Machen, J.G., The Virgin Birth of Christ, Harper Brothers (New York), 1930. See also John Piper’s article Who Was Jesus’ Grandfather? desiringgod.org/articles/who-was-jesus-grandfather, 18 November 1997. Return to text.

- The Greek letter nu (ν) is used, in some forms of Greek, similar to the way English uses a/an before words with or without a vowel. In this case, however, writers can append the letter nu to the end of a word to avoid doubling consonants at the end of one word and the beginning of another. This usage was not standardized, however, so copyists would often use one word form or the other as they saw fit. Among all extant Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, the majority of textual variants can be attributed to the moveable nu. In other words, this is a non-issue as far as textual preservation is concerned. Return to text.

- A recension is a critical revision of a scholarly work. To call the SP a recension means that it has been heavily edited and does not, therefore, reflect the original wording. This is true even though it is written in Hebrew. Return to text.

- What is the Septuagint? How Does It Explain Archaeological Chronology? - Dr. Doug Petrovich, youtu.be/w8BqXrBzgVY. Additional note: Carbon dating is a major problem in archaeology, and Petrovich was right to point out how the offset between the secular dates and the carbon clock increases as one goes back in history. But the answer is probably not that, as he says, the rate of decay has changed. Instead, the earth’s magnetic field has been decreasing exponentially since we started measuring it. If the field was much stronger in the past, the magnetic shielding from cosmic rays would have been stronger. With fewer of these energetic, charged particles striking the upper atmosphere, there would necessarily be less carbon-14 in the early atmosphere. Thus, for very old things, the carbon-14 clock will make things appear more ancient than they actually are. After accounting for this, ancient history collapses into a much shorter timespan. He acknowledges this, but the implications are more profound than most people realize. Return to text.

- Chariots in Ancient Egypt, ancientegyptonline.co.uk/chariots/, accessed 8 October 2021. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.