Journal of Creation 34(1):32–35, April 2020

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Academia and the press as the bad guys

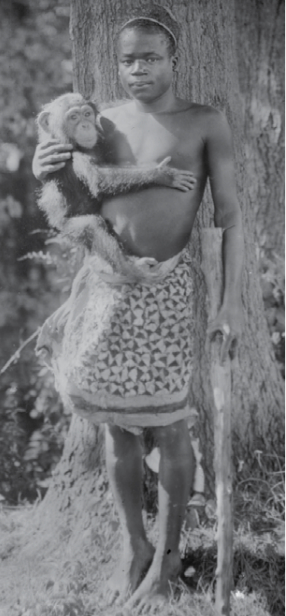

A review of Spectacle: The astonishing life of Ota Benga by Pamela Newkirk

Amistad, New York, 2015

I have previously written about Ota Benga, the pygmy put on display in a zoo, but have since located research by several historians that sheds much new light on this tragic historical event.1 The new research has corrected a major shortcoming of the major past work on the event co-written by Phillips Verner Bradford, the grandson of the man who brought Ota to America.2 The new book about the case, reviewed here, shows Samuel Verner in a very different, and far less favourable, light. The author is Pamela Newkirk, an award-winning journalist and professor of journalism at New York University.

We now have a much better understanding of some of the major events in the case, such as how his experience of being caged in the zoo seriously affected Ota emotionally. Furthermore, Newkirk documents in detail both the academic community’s open support for his display in the zoo and their opposition against the movement to set him free.

The Ota Benga case

Ota Benga, a 100-pound, 1.5m (4 ft 11 in) tall 23-year-old pygmy from Africa, was brought to the 1904 Saint Louis, Missouri, World’s Fair to be put on display as an inferior species of human in an ‘anthropology’ exhibit, ‘The Pygmies’. Both children and adults, described by the scientists as “subhuman, cannibalistic dwarfs” were captured in Africa so as to be exploited in the anthropology exhibits (p. 138). Ota was only one of a total of several thousand persons exhibited in the anthropology exhibits, and the pygmies were one of the most popular parts of the entire exhibit (p. 129). This was partly because pygmies were among the smallest in size, closer to a chimp than any other large people group known then. They were also claimed by the persons directing the exhibits to be one of the most primitive and ‘least advanced’ people known then (p. 129). The inferior race headlines about pygmies soon filled the local papers, such as one that declared the “Pygmies Demand a Monkey Diet” (p. 126).

The seven-month run of the anthropology exhibit was a smashing success. An estimated 12 million visitors paid to get in, and the often-cited total attendance was close to 20 million. The anthropology exhibits of primitive tribes would today correctly be viewed as insensitive, even abhorrent, racist displays. In turn-of-the-century America they were viewed as an academic study of our ancestors, who were not quite fully human. After the World’s Fair ended, Ota was eventually housed at the New York City Bronx Zoo with the primates in the primate house. He was displayed with the monkeys as ‘the missing link’ between human and apes. In the eyes of many evolutionists, he was clear proof of Darwin’s theory of evolution. The question has always been:

“‘Ist das ein Mensch?’ Is it a man?3—one woman asked in German … Could this caged creature be … the incarnation of one of the characters in best-selling books like … The Negro a Beast, published in 1900, or the ‘half child, half animal’, described in Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman, published the previous year, ‘whose speech knows no word of love, whose passions, once aroused, are as the fury of the tiger’? Could he be the missing link, the species bridging man and ape that preoccupied leading scholars?” (p. 9).

For example, Scientific American described Ota as ‘a cannibal’ by an author who “put his unscientific ideas and racial biases on full display [claiming]… ‘Their faces are coarse, features brutal, and [display] evidence of intelligence of an extremely low order’” (p. 132).

Ota’s suffering during his confinement

In contrast to Bradford, Professor Newkirk painted a very different picture of Ota Benga’s experience in the monkey house as proof of evolution. When Ota was placed in the monkey cage, he was, Newkirk claimed, forced to endure “the gawking of spectators utterly indifferent to his feelings. They howled. Gasped. Gaped. Pointed. Jeered. Benga frequently walked to the door with eyes pleading for his keepers to release him from public view” (p. 12). Ota “could feel both the sting of their scorn and the pang of their pity” (p. 12). According to Professor Gump, and documented by psychological research, Ota’s experience was a “searing, painful experience … not substantially different from the effects of physical torture.”4

This research helps to understand Ota’s response as he endured the gawking of spectators who appeared utterly indifferent to his feelings, which would be expected if he was not fully human, which many believed was the case. One motive of those clergymen who wanted to free Ota was their observation that he was fully human and his “sadness was palpable” (p. 33). Evidence also exists that later in life Ota suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome due to “the trauma of being caged, heckled, and attacked at the zoo … by those determined to prove he belonged to an inferior species” (pp. 189, 198).

Scientists’ support for confinement

Professor Newkirk did not hold back concerning the ringleaders of the event, especially the scientists who caged him for public display so that the world could see with their own eyes what they labelled a creature less evolved than modern humans. Not unexpectedly, Ota drew large crowds and earned a great deal of money for the zoo from visitors who wanted to see for themselves this living proof of evolution. The fact is, the ‘exhibit’ was:

“… on the respectable grounds of a world-class zoological park [and] had been sanctioned by Hornaday, one of the world’s leading zoologists, and by Henry Fairfield Osborn, among his era’s most eminent scientists. As an undergraduate at Princeton University, Osborn had spent three months at Cambridge University under the tutelage of the famous British zoologist Francis Balfour; and a summer at London’s Royal College of Science with biologist Thomas Huxley, who became known as ‘Darwin’s bulldog’ for his fierce championship of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Osborn went on to earn a doctor of science degree from Princeton, where for twelve years he taught biology and comparative anatomy” (pp. 13–14).

Furthermore, Ota was a Bushman, a “race that scientists do not rate high on the human scale” of evolution. Nonetheless, to the average non-scientific sightseers in the crowd there was “something about the display that was unpleasant” (p. 13). Newkirk detailed how leading academics, many with degrees from Ivy league colleges, including Princeton and Harvard, actively supported racism based on evolution. She documented that the fight to release Ota from the cage was openly opposed by many powerful, famous academics. Their opposition to helping Ota was openly due to their Darwinian worldview. These leading academics

“… applied Darwin’s evolutionary theory—and the notion of survival of the fittest—to race, insisting that it … explained the plight of blacks and the supposed racial superiority of whites. … Hornaday said that while he did in fact support Darwin’s theory … ‘I am giving the exhibition purely as an ethnological exhibit’” (p. 35).

This case is not only about Ota Benga, but the racist society that existed in America when Ota was alive in the early 1900s. Rev. Dr Robert MacArthur, the white pastor of the large Manhattan Calvary Baptist Church (1910 membership: 2,300), led the fight against the scientists, taking on not only the director of the zoo, Dr Hornaday, but he also challenged

“… an esteemed institution whose cofounders included a president of the United States; an eminent scientist; and the high-society lawyer Madison Grant, the Zoological Society’s secretary. Moreover, Hornaday was himself the nation’s foremost zoologist and a close acquaintance of President Theodore Roosevelt” (p. 29).

Anthropologist Madison Grant, a cofounder of the zoo Hornaday directed, authored the enormously influential 1916 racist book titled The Passing of the Great Race,5 which openly

“… advocated cleansing America of ‘inferior races’ through birth control, anti-miscegenation … racial segregation laws, and mass sterilization. He argued that Negroes were so inferior to Nordic whites that they were separate species and infamously warned: ‘… the result of the mixture of two races, in the long run, gives us a race reverting to the more ancient, … lower type. The cross between a white man and an Indian is an Indian; the cross between a white man and a negro is a negro; the cross between a white man and a Hindu is a Hindu; and the cross between any of the three European races and a Jew is a Jew’” (p. 43).

Grant’s book also influenced the development of Adolf Hitler’s racist ideas.6 The list of those who did nothing to help Ota, and even resisted efforts by others to help him, included President Theodore Roosevelt and President Woodrow Wilson. Furthermore, “Echoing the sentiments of the esteemed Men of Science”, the New York Times editors were “confounded by the protests”, explaining that they did not

“… understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter … Ota Benga … is a normal specimen of his race or tribe … . Whether they are held to be illustrations of arrested development, and really closer to the anthropoid apes than the other African savages, or whether they are viewed as the degenerate descendants of ordinary negroes, they are of equal interest to the student of ethnology, and can be studied with profit” (p. 38).

Divesting Benga of human emotion, and ignoring the many accounts of his distress, was the view reported in a New York Times editorial that claimed it was absurd that Benga could be suffering or experiencing humiliation because pygmies

“… are very low in the human scale, and the suggestion that Benga should be in a school instead of a cage ignores the high probability that school would be a place of torture to him. … The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education of books is now far out of date” (p. 38).

This was the conclusion “espoused by generations of leading scientists”, including Louis Agassiz, the Harvard professor who “was arguably America’s most venerated scientist, [and] had for more than two decades insisted that blacks were a separate species, a ‘degraded and degenerate race’”.7 In his address as outgoing president of The American Association for the Advancement of Science, University of Pennsylvania professor of linguistics and archaeology, Daniel Garrison Brinton

“… rebutted claims that education and opportunity accounted for varying levels of achievement along racial lines [concluding]; The black, the brown, and the red races differ anatomically so much from the white, especially in their splanchnic [internal, especially abdominal] organs, that even with equal cerebral capacity they never could rival its results by equal efforts …’” (p. 38).

The New York Evening Post’s headline was typical of this sentiment: “A Pygmy among the primates.” The Minneapolis Journal went further, proclaiming that Ota “is about as near an approach to the missing link as any human species yet found” (p. 72). The Ota Benga case was not by any means unique. One of many examples included a South African woman, Sara(h) Baartman, who was exhibited barely clad throughout London and Paris for years as the “Hottentot Venus”.8 She was also touted by scientists as the link between humans and the lower apes.9 The famous scientist Georges Cuvier, the founding father of the vertebrate paleontology field, performed an autopsy on her

“… and concluded that she and the so-called Hottentots were more akin to apes than to humans. He made a cast of Baartman’s body and preserved her brain, genitals, and skeleton, ensuring that even in death, she’d draw a crowd. While Benga was being exhibited in a monkey house cage, Baartman’s remains—her brain, genitals, and skeleton—were still on display in case number 33 at the Paris Musée del l’Homme” (pp. 16–17).

Most people today “find such behavior both racist and morally contemptible”, but in “the era’s elite white circles Cuvier was generally considered an embodiment of scientific truth” (p. 37). This was despite the fact that Cuvier had met her when she was alive, and then noted her intelligence, ability to speak several languages, and skill with a musical instrument; and even thought that her hands and feet were pretty. Long after the death of Baartman,

“… human zoos celebrating Europeans’ conquest of purportedly primitive people remained popular in Europe; these included zoos in Hamburg, Barcelona, and Milan. Carl Hagenbeck … exhibited Samoan and Sami people to great success in 1874. So popular was his 1876 exhibit of Egyptian Nubians that it toured Berlin, Paris, and London. A year later Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, director of the Jardin Zoologique d’Acclimation in Paris, organized exhibits of Nubians and Inuit seen by one million people; and in 1885, King Leopold II of Belgium exhibited several hundred of his newly conquered Congolese people in Brussels to appreciative crowds” (p. 17).

Scientific opposition to his confinement

Professor Franz Boas (1858–1942) was one of the very few scientists then that was opposed to the racism based on evolutionary biology. He is regarded as one of the most prominent opponents of the then-dominant scientific racist ideology, the idea that race is a biological concept and that human behaviour is best understood as caused largely by biology. Boas probably did more to combat race prejudice than any other person of his day.10

Boas was appointed lecturer in physical anthropology at Columbia University in 1896 and was promoted to Professor of Anthropology in 1899. For much of his career, he spoke out against Darwinian eugenics and the racism that it birthed. Unfortunately, Boas “was drowned out by a chorus of American and European scientists who ranked the world’s races … with Europeans at the top and Africans at the bottom” (pp. 44–45). Because Boas was a German Jew, it was alleged that his conclusions about race were neither objective nor factual. It didn’t help that he undermined his own arguments by dogmatizing cultural relativism, which is antithetical to objective right and wrong.

Other opposition to Ota’s confinement

The few persons determined to stop the mistreatment of Ota included mostly black Christian ministers led by a white man, Rev. Robert Stuart MacArthur, all of whom opposed Darwinism, and thus were against putting Ota on display to prove a worldview they believed was both morally and scientifically wrong. The black ministers who supported freeing Ota concluded, according to a 2 September 1906 report in the New York Times: “We think we can do better for him than make an exhibition of him—an exhibition as it seems to us to corroborate the theory of evolution—the Darwinian theory”; a theory, they noted, they do not accept (p. 35).

Ironically, Hornaday “insisted that the exhibit was in keeping with human exhibitions in Europe” noting the “Continent’s indisputable status as the world’s paragon of culture and civilization” (p. 16). As the opposition by the Baptist ministers increased, the New York Times finally took note with the headline, “Man and monkey show disapproved by clergy”. Eventually, this turmoil, including protest from the creationist ministers, resulted in Ota’s release. In the end, Ota committed suicide. One can only wonder about the possible influence his experience of being displayed in a zoo with monkeys had on his tragic end.

References and notes

- Bergman, J., Ota Benga: The story of the pygmy on display in a zoo! CRSQ 30 (3):140–149, 1993. Return to text.

- Bradford, P.V., Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the zoo, St Martin’s Press, New York, 1992. Return to text.

- In this citation, the word Mensch would have more appropriately been translated ‘human being’. Return to text.

- Gump, J.P., A white therapist and an African American patient—Shame in the therapeutic dyad: commentary on paper by Neil Altman, Psychoanalytic Dialogue 10(4):619–632, 1 Jul 2000. Return to text.

- Grant, M., The Passing of the Great Race, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1916. Return to text.

- Spiro, J.P., Defending the Master Race: Conservation, eugenics, and the legacy of Madison Grant, University Press of New England, Burlington, VT, pp. 15–66, 2009; Ryback, T.W., A Disquieting Book from Hitler’s Library, International Herald Tribune, p. 10, 8 December 2011. Return to text.

- Baker, L., Savage Inequality: anthropology in the erosion of the Fifteenth Amendment, Transforming Anthropology 5(11):28–33, 1994. Return to text.

- Holmes, R., African Queen: The real life of the Hottentot Venus, Random House, New York, 2007. Return to text.

- Crais, C.C. and Scully, P., Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A ghost story and a biography, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2010. 10. Gossett, T., Race: The history of an idea in America, Oxford University Press, New York, p. 418, 1963. Return to text.

- Gossett, T., Race: The history of an idea in America, Oxford University Press, New York, p. 418, 1963. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.